To Kill a Mockingbird – Harper Lee

Shoot all the bluejays you want, if you can hit ‘em, but remember it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.

Set during the height of the Great Depression of the 1930s, To Kill a Mockingbird, is the tale of an innocent childhood in a sleepy southern town rocked by scandal. When Lawyer Atticus Finch chooses to defend a black man charged with the rape of a white girl he exposes his children to the reality of racism and stereotyping. The story, which is told through the eyes of Atticus’ six-year-old daughter, Jean-Louise ‘Scout’ Finch, sheds an amusing unfettered light on the irrationality of deep-south traditions surrounding race and class in the mid-1930s. At its heart, To Kill a Mockingbird is a classic coming-of-age tale, which went on to become one of the most famed anti-racist novels of the 20th century. Today the book is widely regarded as a one of the masterpieces of American Literature.

Set during the height of the Great Depression of the 1930s, To Kill a Mockingbird, is the tale of an innocent childhood in a sleepy southern town rocked by scandal. When Lawyer Atticus Finch chooses to defend a black man charged with the rape of a white girl he exposes his children to the reality of racism and stereotyping. The story, which is told through the eyes of Atticus’ six-year-old daughter, Jean-Louise ‘Scout’ Finch, sheds an amusing unfettered light on the irrationality of deep-south traditions surrounding race and class in the mid-1930s. At its heart, To Kill a Mockingbird is a classic coming-of-age tale, which went on to become one of the most famed anti-racist novels of the 20th century. Today the book is widely regarded as a one of the masterpieces of American Literature.

It’s no wonder then, that the release of Lee’s second novel, Go Set a Watchman, fifty-five years after To Kill a Mockingbird, was met with such excitement.

Go Set a Watchman – Harper Lee

You deny them hope. Any man in this world, Atticus, any man who has a head and arms and legs, was born with hope in his heart. You won’t find that in the Constitution, I picked that up in church somewhere. They are simple people, most of them, but that doesn’t make them subhuman.

Go Set a Watchman takes up with twenty-six-year-old Jean-Louise, as she returns to Maycomb to visit her now ageing father, Atticus. Set against the backdrop of the civil rights movement, Go Set a Watchman delves into the raw truth of the political turmoil which marred the Southern United States of the 1950s. Jean-Louise’s homecoming, far from being an idyllic break in the country, takes an unsettling turn, as racial tensions rippling through the town come to her attention and she learns some troubling truths about the friends and family close to her heart. As she struggles to comprehend the changes occurring around her, Jean-Louise embarks on a life-changing journey guided by her own conscience.

Go Set a Watchman takes up with twenty-six-year-old Jean-Louise, as she returns to Maycomb to visit her now ageing father, Atticus. Set against the backdrop of the civil rights movement, Go Set a Watchman delves into the raw truth of the political turmoil which marred the Southern United States of the 1950s. Jean-Louise’s homecoming, far from being an idyllic break in the country, takes an unsettling turn, as racial tensions rippling through the town come to her attention and she learns some troubling truths about the friends and family close to her heart. As she struggles to comprehend the changes occurring around her, Jean-Louise embarks on a life-changing journey guided by her own conscience.

By now, you will have no doubt read your fair share of reviews and criticism of Go Set a Watchman. Before I get into the controversy surrounding the book’s release, and subsequent criticisms of the book itself, I first want to tell you why I loved the book.

The structure of Go Set a Watchman is so completely different to To Kill a Mockingbird; I’ve heard it called jarring, and awkward, but I found it refreshing. The novel is told in the third person, but still awards an amazing insight into the minds of the central characters, with large sections of text given over to Jean-Louise’s hilarious internal monologue, particularly when she finds herself at odds with her insufferable aunt (‘Jehovah!’). As a reader you are able to witness Jean-Louise without being restricted by seeing everything through her eyes. I loved the effect that this had and I feel it allowed for a deeper understanding of her character. The quick fisted child from To Kill a Mockingbird may have aged some, but her personality and morals remain as rigid as ever. Even as an adult she is far happier in slacks than a skirt, and more than willing to speak her mind to anyone who disapproves. Twenty years on, and the adult Jean-Louise is still a force to be reckoned with.

I also loved the amount of time Lee gave to looking into Jean-Louise’s life in the years in between To Kill a Mockingbird and Go Set a Watchman. I loved Jean-Louise’s internal anecdotes about her childhood, in particular the nine month’s spent thinking she was pregnant after being wrongly advised about the birds and the bees by an older girl. Watching the whole debacle unfold is hilarious, but none so much as the exchange between Jean-Louise and Calpurnia when she finally confesses her horrible secret:

“I’m going to have a baby!” she sobbed.

“When?”

“Tomorrow!”

Calpurnia said, “As sure as the sweet Jesus was born, baby. Get this in your head right now, you ain’t pregnant and you never were. That ain’t the way it is.”

“Well if I ain’t, then what am I?”

“With all your book learnin’, you are the most ignorant child I ever did see…” Her voice trailed off. “… but I don’t reckon you really ever had a chance.”

Little gems like this give Go Set a Watchman a really human feel, which I absolutely loved. It is one thing to witness a character’s story as it unfolds, but another to observe a character revisiting their past. The Jean-Louise of To Kill a Mockingbird exists only in the present moment, whereas the adult Jean-Louise transcends time periods to enable a fuller understanding of the complexities of her character.

Now, on to the controversy.

I know a lot of people are of the opinion that Lee was manipulated into granting permission for the release of Go Set a Watchman, and I’m sure nothing I say will change this, but I, personally, do not believe that this is the case. Firstly, friends and family close to Lee have outright denied that this claim – but this is not the only reason I choose to believe that Lee wanted the book to be published. I think that the presence of anomalies within the text, specifically with regards to the outcome of the Tom Robinson case in To Kill a Mockingbird, suggest that Lee had the definitive choice when it came to publishing the book. For me, the presence of such anomalies show that Lee wanted the book to be seen and to be viewed as it was; true to the time it was written, and not as a sequel to To Kill a Mockingbird. If the release of Go Set a Watchman was nothing more than a money-making plan at the expense of a fragile old lady I do not think this would be the case.

The circumstances surrounding the publication of Go Set a Watchman are not the only thing awarding the book negative media attention. I have read so many opinion pieces that suggest that the book ruins To Kill a Mockingbird and taints the Atticus Finch that we all knew and loved. One US bookstore even offered refunds to anyone who purchased the novel from them, on the ground that their advertising it as ‘nice summer read’ was unquestionably false. This, again, I do not agree with.

When I read To Kill a Mockingbird I fell completely in love with Atticus, and there is no doubt in my mind that the Atticus Finch in Go Set a Watchman is fundamentally different. But did this new portrayal of his character ruin the former impression I had? No, of course not. The Atticus Finch of To Kill a Mockingbird still exists, and nothing will ever change that. Go Set A Watchman may be set 20 years after To Kill a Mockingbird, but it was never intended to serve as a sequel.

The time portrayed in Go Set a Watchman can’t be viewed in a vacuum, but neither should it be completely judged based on To Kill a Mockingbird. The two books are fundamentally different. One gave birth to the other. Go Set a Watchman in itself is an incredible look at the time in which it was written, allowing for amazing insight into the Southern United States of the 1950s.

Would Go Set a Watchman have been accepted by a publisher now were it not for To Kill a Mockingbird? I don’t know. Maybe not. The novel is certainly not as ground-breaking as To Kill a Mockingbird – but is that really surprising? It is the history of the book that is really fascinating. As readers we have been given the chance to read the first draft of one of the most famous books ever written. In reading Go Set a Watchman you are given an incredible insight into Harper Lee’s writing process. Needless to say, as a booklover, and a fan of To Kill a Mockingbird, I found Go Set a Watchman to be an incredibly interesting and exciting book to read.

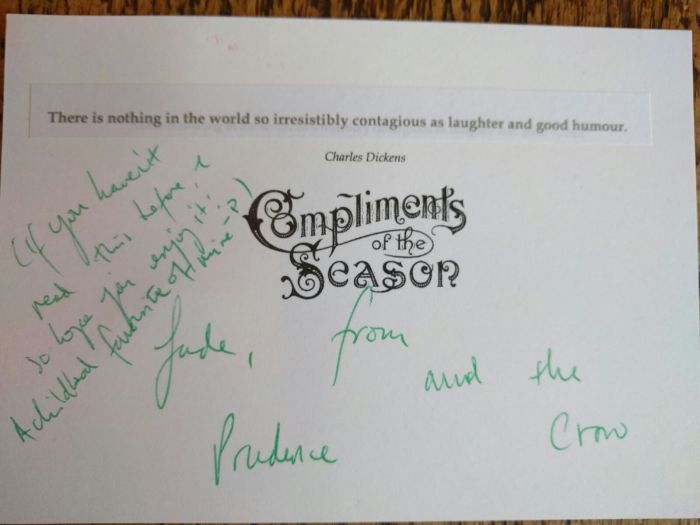

If you haven’t yet read Go Set a Watchman, and haven’t been put off by all the negative media coverage than I have good news for you. I have an extra copy of the book up for grabs for one lucky reader.

Simply comment on this blog post by Friday 4th September, to be in with a chance of winning.

Happy commenting!

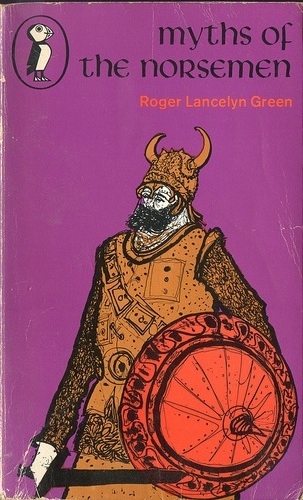

In Myths of the Norsemen, Roger Lancelyn Green has taken the surviving Norse myths, collected from Old Norse poems and tales, and retold them as a single, continuous narrative. The entire Norse timeline is covered, offering a complete and concise history of the Aesir and their dealings with the Giants of Utgard, from the planting of The World Tree, Yggdrasill, right up to the last great battle Ragnarok.

In Myths of the Norsemen, Roger Lancelyn Green has taken the surviving Norse myths, collected from Old Norse poems and tales, and retold them as a single, continuous narrative. The entire Norse timeline is covered, offering a complete and concise history of the Aesir and their dealings with the Giants of Utgard, from the planting of The World Tree, Yggdrasill, right up to the last great battle Ragnarok.